Finishing Process Approval vs. Production Finishing Calibration Lock Timing Gap in Custom Stationery Procurement

When a procurement team signs off on a sample of custom embossed leather notebooks or foil-stamped executive pen sets, the finishing quality is usually the single most influential factor in that approval. The depth of the blind debossing, the crisp metallic edge of the gold foil logo, the smooth tactile transition between coated and uncoated surfaces—these are the details that convince stakeholders the supplier can deliver. In practice, this is often where customization process decisions around finishing specifications start to be misjudged. The sample finishing was produced under conditions that bear almost no resemblance to the production finishing environment, and the gap between sample finishing approval and production finishing calibration lock—typically 13 to 20 days—introduces a category of timeline risk that procurement teams rarely account for in their delivery calculations.

The fundamental issue is one of equipment translation. When a factory produces 10 to 15 sample units of a custom stationery product, the finishing work is performed on a manual or semi-automatic press. An experienced operator loads each piece individually, adjusts the platen temperature by feel, modifies the dwell time based on how the material responds, and applies pressure with the kind of micro-corrections that come from years of craft experience. If the first impression on a leather journal cover shows slightly shallow embossing, the operator increases pressure by 5-8% on the next piece. If the foil adhesion on a pen barrel appears marginally weak, the operator raises the temperature by 3-4 degrees Celsius and extends the dwell time by half a second. Each of the 10-15 sample units receives this individual attention, and the result is a set of samples where every piece looks exceptional. The procurement team reviews these samples, compares them against the design brief, and issues approval on Day 15, believing that the finishing quality has been locked for the entire production run.

What procurement teams do not observe is the translation process that occurs between Day 15 and Day 28-35, when the factory must convert those manually-achieved finishing results into automated production parameters. The production finishing environment operates under fundamentally different physics. Instead of a manual press processing one piece every 2-3 minutes with operator adjustment, the production line runs a high-speed automated press at 1.2 to 1.8 seconds per impression across 5,000 or more units. The operator does not touch individual pieces. Instead, the machine runs on fixed parameters—a locked temperature setting, a locked pressure value, a locked dwell time—and every unit in the production run receives identical treatment regardless of minor material variations across the batch.

The first stage of this invisible calibration window, typically Day 16-18, involves equipment compatibility assessment. The sample finishing was likely performed on Machine A—a flatbed semi-automatic press with a 30×40 centimeter platen, capable of precise single-unit positioning. The production run, however, will be executed on Machine B—a rotary or cylinder press with continuous feed capability, designed for throughput rather than individual precision. These two machines have different thermal profiles (Machine A heats evenly across a small platen; Machine B has temperature gradients across a larger cylinder surface), different pressure distribution patterns (uniform versus linear contact), and different dwell time characteristics (static versus rolling contact). The factory's production engineering team must evaluate whether Machine B can physically replicate the finishing quality achieved on Machine A, and if not, determine which parameter adjustments are necessary to achieve an acceptable approximation.

The second stage, Day 19-22, addresses bulk finishing material procurement and batch testing. This is where the cost structure of sample versus production finishing creates its most significant quality divergence. The sample foil—used for the gold logo stamping on those 10-15 approval units—was typically sourced from a premium small roll, often a Japanese or German specialty foil priced at $40-50 per roll, with exceptional adhesion characteristics, consistent color density, and tight thickness tolerances. The production foil, by contrast, comes from a bulk roll sourced from a cost-competitive supplier, priced at $15-20 per roll, with broader tolerance ranges on adhesion strength, color density, and thickness uniformity. The factory cannot use the premium sample foil for 5,000 units—the cost differential alone ($45 versus $18 per roll, with each roll covering approximately 200-300 impressions) would add $0.45-0.90 per unit to the finishing cost, which on a 5,000-unit order represents $2,250-4,500 in additional material expense that was not included in the original quotation.

The bulk foil arrives at the factory on Day 20-21, and the production engineering team immediately runs adhesion tests against the substrate material. The sample foil adhered at 135°C with 0.8 seconds dwell time on the sample leather. The bulk foil, with its different adhesive layer composition, may require 142°C with 1.0 seconds dwell time to achieve comparable adhesion on the same leather—but the leather itself is now from the bulk supplier rather than the sample supplier, with slightly different surface texture and moisture content that further affects foil transfer characteristics. The factory must run 50-100 test impressions to establish the optimal parameter window for the specific combination of bulk foil + bulk leather + production machine, a process that consumes 1-2 days of engineering time and 200-300 units worth of test material.

The third stage, Day 23-26, is the production parameter calibration trial sequence—and this is where the most significant timeline risk accumulates. The factory runs what are internally called T1, T2, and T3 trials, each representing a full calibration attempt on the production press. The T1 trial sets initial parameters based on the engineering team's calculations from the adhesion tests: temperature at 142°C, pressure at 85 kN, dwell time at 1.0 seconds, feed speed at 2,400 impressions per hour. The T1 output is evaluated against the approved sample. Common T1 outcomes include: foil bleeding beyond design edges (temperature too high by 3-5°C), incomplete foil transfer in fine detail areas (pressure insufficient by 8-12%), inconsistent embossing depth across the platen width (uneven pressure distribution requiring shimming), or foil color appearing slightly lighter than the sample (bulk foil has 5-8% lower pigment density than premium sample foil).

The T2 trial corrects the T1 deficiencies: temperature reduced to 139°C, pressure increased to 92 kN with 0.3mm shim added to the left side of the platen, dwell time extended to 1.1 seconds. The T2 output shows improved edge definition and more consistent embossing depth, but the foil adhesion in the center of the logo is now marginally weaker than the edges—a consequence of the pressure redistribution from shimming. The T3 trial further refines: pressure adjusted to 89 kN with the shim repositioned, temperature held at 139°C, dwell time at 1.1 seconds, and a pre-heat cycle added to stabilize the platen temperature before each production batch. The T3 output is evaluated as "within acceptable production tolerance"—meaning 95-97% of impressions will fall within the quality specification, with 3-5% requiring rework or rejection.

This 95-97% acceptance rate is itself a source of misjudgment. The approved sample represented 100% quality—every piece was individually crafted to perfection by a skilled operator. The production run, by definition, cannot achieve 100% consistency across 5,000 automated impressions. Temperature drift over a 4-hour production run (the platen temperature may shift ±5°C as the machine heats and cools through cycles), material variation within the bulk leather batch (moisture content differences of 2-3% between hides affect foil adhesion), and foil roll tension changes as the roll diameter decreases during the run (affecting foil registration and coverage)—all of these variables introduce unit-to-unit variation that did not exist in the sample production environment. Procurement teams who approved a "perfect" sample will receive a production batch where 95-97% of units meet specification and 3-5% show minor finishing variations that would not have passed sample-stage scrutiny.

The fourth stage, Day 27-30, involves production finishing validation, where the factory submits T3 trial output to the buyer for production-grade finishing approval. This is a critical decision point that many procurement teams are unprepared for. The T3 samples will not look identical to the original approved samples. The embossing may be 0.1-0.2mm shallower (production press applies rolling pressure rather than static pressure), the foil color may be 5-8% less saturated (bulk foil versus premium foil), and the edge definition may show slight softening on curves (higher speed reduces dwell time precision on complex geometries). The factory presents these as "within production tolerance," but procurement teams—who approved based on the sample's perfection—may reject the T3 output and request further calibration, adding another 5-7 day cycle to the timeline.

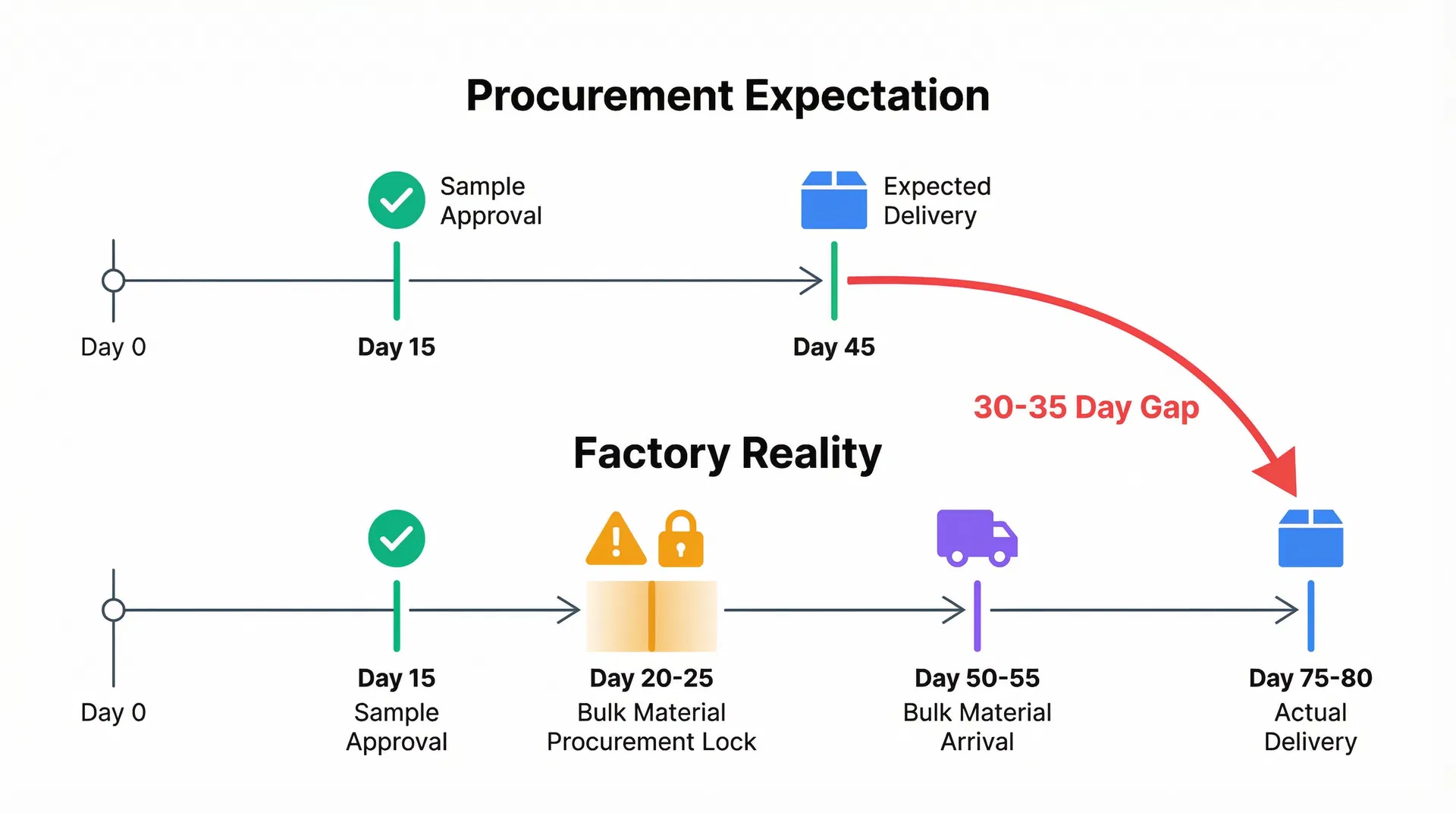

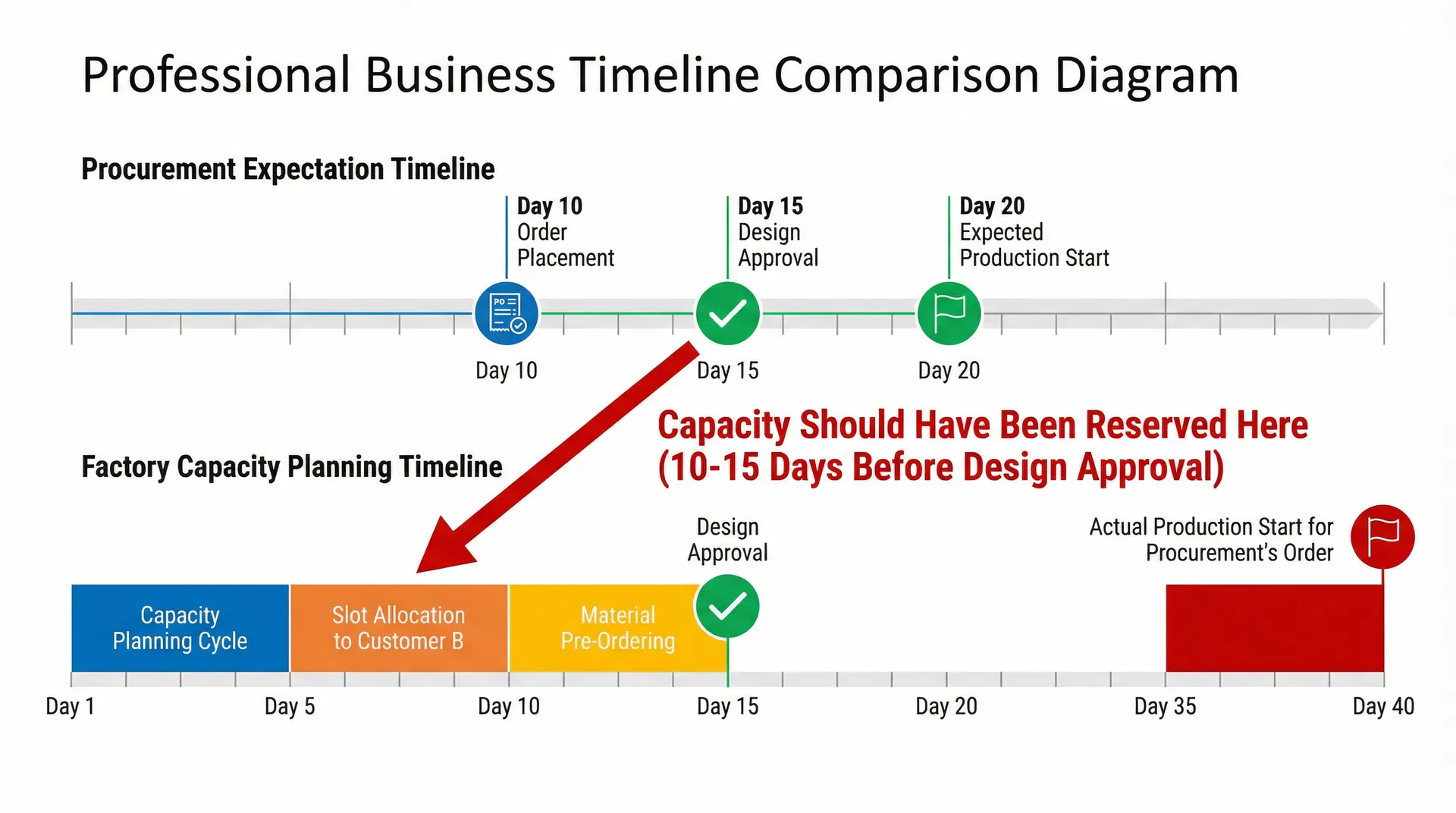

The cumulative effect of this four-stage calibration process is a 13-20 day window between sample finishing approval (Day 15) and production finishing calibration lock (Day 28-35) that procurement teams do not include in their delivery calculations. A procurement team that approves finishing on Day 15 and expects 35 days of production time will calculate delivery at Day 50. The factory, which cannot begin production finishing until calibration is locked on Day 28-35, calculates 35 days of production from that point, arriving at Day 63-70. The 13-20 day gap appears as "factory delay" in procurement's tracking system, but from the factory's perspective, it represents the minimum engineering time required to translate a manually-crafted sample into automated production parameters.

The challenge intensifies with multi-technique finishing—orders that combine embossing, foil stamping, and UV spot coating on the same product. Each finishing technique requires its own calibration sequence, and the techniques interact: embossing depth affects foil adhesion (deeper embossing creates uneven surfaces that reduce foil contact area), foil thickness affects UV coating adhesion (metallic foil surfaces have different surface energy than uncoated leather), and UV coating application affects subsequent handling (curing time, stacking pressure, packaging compatibility). A three-technique finishing specification may require 6-9 calibration trials instead of 3, extending the calibration window to 20-30 days and pushing actual delivery to Day 75-85 against a procurement expectation of Day 50.

For procurement teams managing custom stationery and corporate gift orders in the UAE market, where executive presentation quality is non-negotiable and brand standards are rigorously enforced, this finishing calibration gap represents one of the most consequential blind spots in customization workflows. The approved sample creates an implicit quality benchmark that the production environment cannot precisely replicate—not because of factory incompetence, but because of the fundamental physics difference between manual craft production and automated mass production. The sample was a sculpture; the production run is a manufacturing process. Both produce the same product, but the tolerance envelope around "acceptable quality" widens significantly when moving from one environment to the other.

The most effective approach to managing this gap involves restructuring the sample approval process to include a "production simulation" stage. Instead of producing samples on a manual press and then translating to production equipment, the factory produces the initial samples on the actual production press using production-grade materials. This approach adds 5-8 days to the sample production timeline (the factory must run preliminary calibration before producing approval samples) but eliminates the post-approval calibration window entirely. The buyer approves samples that accurately represent production-grade finishing quality, and approval on Day 20-23 (instead of Day 15) genuinely locks production parameters, allowing manufacturing to begin immediately. The net timeline impact is neutral or slightly positive: 5-8 days added to sample production, 13-20 days removed from post-approval calibration, resulting in 5-12 days of net timeline reduction.

However, this production-simulation approach requires the factory to commit production press time to sample production—time that could otherwise be used for revenue-generating production runs. For a factory running at 80-90% capacity utilization, dedicating 2-3 days of production press time to produce 15 sample units represents a significant opportunity cost. Most factories will only offer this approach for orders above a certain volume threshold (typically 3,000-5,000 units) where the post-approval calibration savings justify the upfront production press allocation. For smaller orders, the manual sample + post-approval calibration sequence remains the default workflow, and procurement teams must incorporate the 13-20 day calibration window into their delivery timeline calculations.

The gap between sample finishing approval and production finishing calibration lock is not a negotiable variable—it is a structural characteristic of any manufacturing process that transitions from craft-scale to production-scale finishing. The temperature, pressure, and dwell time parameters that produce a perfect foil stamp on a manual press at 2-3 minutes per piece cannot be directly transferred to an automated press running at 1.2-1.8 seconds per piece. The foil that adheres flawlessly from a premium small roll does not behave identically when sourced from a bulk roll with different adhesive chemistry. The leather that accepted embossing beautifully in a pre-conditioned sample batch responds differently when processed from a bulk shipment with variable moisture content. Each of these translation steps requires engineering time, test material, and calibration cycles that collectively form the 13-20 day invisible window between what procurement teams consider "finishing approved" and what factories consider "finishing locked for production." Recognizing this window—and building it into delivery commitments from the outset—is the difference between a timeline that holds and one that generates 15-20 days of unexplained delay.